|

The trauma-informed rhetoric has been focused on a medical model of trauma. We have been looking at how the brain is impacted by trauma and ways teachers need to heal students. In addition, a narrow definition of trauma as both deficit and recognizable leaves out the notion that racism and subjugation are traumatic, especially when they occur in schools. We need to shift how we define trauma away from a deficit-based medical model. Also, we need to rethink what we count as trauma so we can recognize race-based traumas in schools and act in opposition to them.

We always talk about what counts as trauma and what counts is usually some form of cognitive and developmental damage from recognizable incidents. What about other factors in the lives of our students are traumatizing, yet don’t look so on the surface? Keep reading to learn how race-based traumas go unnoticed in schools because of our narrow and deficit-based definition of what gets to count as trauma. Our current Conception: Ill-Defined & Problematic

Elizabeth Dutro (2019) wrote, “My concerns are rooted in the flightiness of the word ‘trauma’ and all of the complexities in how it lands on certain children” (p. 3). She went on to explain that trauma-informed researchers and practitioners have yet to agree on what actually counts as trauma. Even so, a predominant definition of trauma is one in which students are seen as damaged and teachers are positioned as their healers. This trauma is also typically thought of to have roots in a recognizable event or series of events. When we narrow our definition to require that children who have experienced trauma are damaged, doing so “makes it difficult to see the whole child, including the knowledge, empathy, and wisdom about life that children bring to their learning” (p. 18). Within such a deficit-based medical model, we risk pathologizing children and their families, that is, we risk making them seem like medical patients in need of some professional healing. Doing so can make working with trauma-affected youth intimidating for teachers, as they feel they are not the right person to meet the child's needs.

Where Deficit-Based Medical Models and Race-Based Models of Trauma Meet

A definition of trauma as rooted in a specific incident or series of incidents can be considered a medical model by thinking of a metaphor. That metaphor is an accident that results in injury. When we have an accident, maybe falling of a jungle gym and breaking a bone, we are immediately treated with medical attention. The medical attention we receive is a predetermined method for treating that specific injury. Over time, the injury heals and we go back to normal. Without that medical attention, our lives could be seriously impacted in a permanent way. The medical model of trauma sees students' brains as damaged and rooted in a specific incident (think injury) or series of incidents. That is, this trauma is recognizable and there are predetermined methods for treating it. These are seen as things that only medical professionals are capable of doing. If teachers become trauma-informed through this model (like I did!), they may see trauma in a concrete manner, don't see themselves as complicit in trauma, and rather see themselves as responsible for healing the child, who wouldn't be able to do so on their own or in their family or community.

When we see trauma through this lens, we miss unrecognizable traumas that result from race-based interactions. What's more, our concept of what counts as normal may pathologize children whose lives are full of unrecognizable traumas and label them through a deficit lens as disabled or defiant. Considering unrecognizable Trauma

In addition to Dutro’s (2019) work, Alvarez et al. (2016) problematized attending only to trauma that is recognizable in that doing so misses the race-based traumas that are prevalent in and out of schools. A medical model of trauma as recognizable (post-war PTSD, physical or sexual abuse, traumatic brain injury, etc.) “invalidates other forms of trauma...the ways that factors such as race and poverty influence trauma” (p. 29). Ongoing racial prejudices that are allowed or even perpetuated by teachers may have the same impact as the experiences of physical abuse. Alvarez et al. (2016) cited Romero and Roberts (2003), saying that “Verbal, race-based assaults led to the same symptoms in students that one might expect to find among survivors of physical abuse, such as depression and isolation” (p. 32).

But Why?

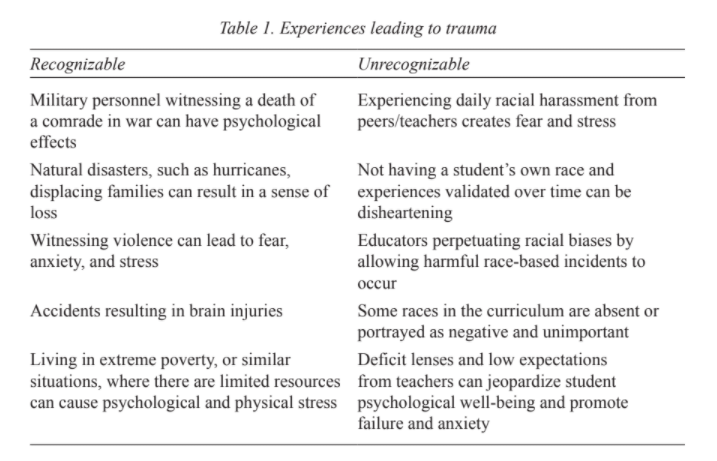

Why does it matter whether we accept race-based traumas as legitimate? If we don’t we can miss some critical indicators of trauma and blind us to what students of color really need from us. Below is a table from Alvarez et al. (2016) that should help you to expand how you view trauma in schools. Stay tuned for future posts to learn what you can and should do about race-based traumas in schools, whether you teach students of color or not!

References:

Alvarez, A., Milner, H. R., & Delale-O'Connor, L. (2016). Race, trauma, and education. In T. Husband (Ed.), But I don't see color (pp. 27-40). Sense Publishers. Dutro, E. (2019). The vulnerable heart of literacy: Centering trauma as powerful pedagogy. Teachers College Press. Romero, A. J., & Roberts, R. E. (2003). Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9(2), 171.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Erin E. Silcox. I'm working on my Ph.D. in Literacy Education, focusing on the intersection of trauma and literacy. I want to deepen our base of knowledge about trauma-informed practices in schools and help teachers apply findings right now. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed